Classical Moments

Important Highlighted Selections of Classical Music

This page contains “moments” of Classical Music that are especially important and engaging. Each “moment” is presented with a snapshot from the score, and an explanation of what to listen for and what makes them great. For many of the moments included below, clicking on the score image will allow you to listen to the music referenced.

From David Bernard:

“A performance of a work is essentially a series of moments that take listeners on a journey through time, with an impact that can be breathtaking, thrilling, shocking and/or simply giving you goosebumps. Our connection with moments we experience in a performance last long after the performance ends, enriching us for a lifetime. Creating these moments in a way that has a profound impact on audiences is the lifelong work of musicians.

This collection contains moments in classical works that have been extremely important to me, presented with a short description of what makes each moment so special from a listener’s point of view. I hope this walk through of what I love in this music inspires more listeners, and ultimately more enthusiasts for classical music.”

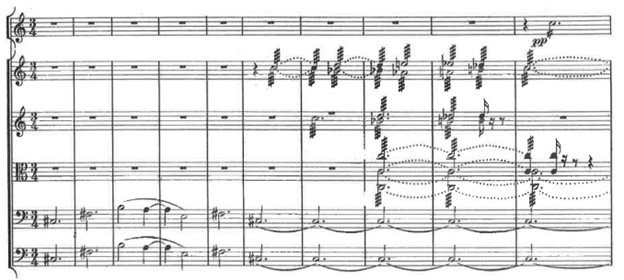

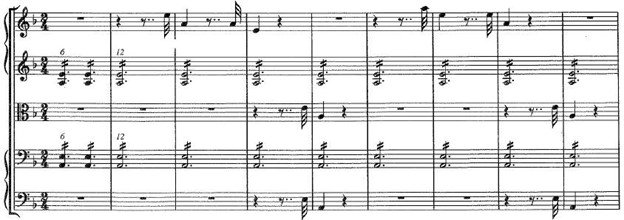

BARTÓK CONCERTO FOR ORCHESTRA, 1ST MOVEMENT: AUSPICIOUS BEGINNINGS

The essence of the entire work is revealed to the listener in the first 10 seconds. Within the rising and falling legato line in the lower strings, followed by the shimmering upper strings and flutes, Bartók carefully embeds the DNA of a new musical language--a language that while highly chromatic and at times dissonant, has a strong coherence and beauty all its own. When composers take such great care in defining the listening experience for their listeners, those listeners are given an unforgettable experience--and this work is an example of how masterful Bartók was at creating this experience. Truly Brilliant Innovation.

BARTÓK CONCERTO FOR ORCHESTRA, 4TH MOVEMENT: CIRCUS IN THE MIST

The children's book "Circus in the Mist" chronicles a journey through a misty forest to a circus and back again using a section of pages made of colorful construction paper (the circus) surrounded by beginning and ending sections of pages made of tracing paper (the misty forest). As you turn each page, you can see the colors of the approaching circus showing through the tracing paper--and as you leave the circus you see the colors disappear.

The fourth movement of Bartók's Concerto for Orchestra sends you on a similar journey. A mysterious and hypnotic dance played by the winds accompanied by ethereal strings takes you to a passionate and lyrical love song played by the violas and violins, ultimately arriving at a raucous and jovial circus featuring clarinets and trombone glissandi. Once the circus show is over, you are brought back the way you came, through the love song and then then right back to the dance, where the movement ends. The music in this movement is so endearing, that as you pass from section to section, you can't help but feel a bit wistful as you see the previous section disappear in the mist of the past.

If you've never heard Bartók's Concerto for Orchestra, give this movement a listen. It is only 4 minutes long, and you will simply love it.

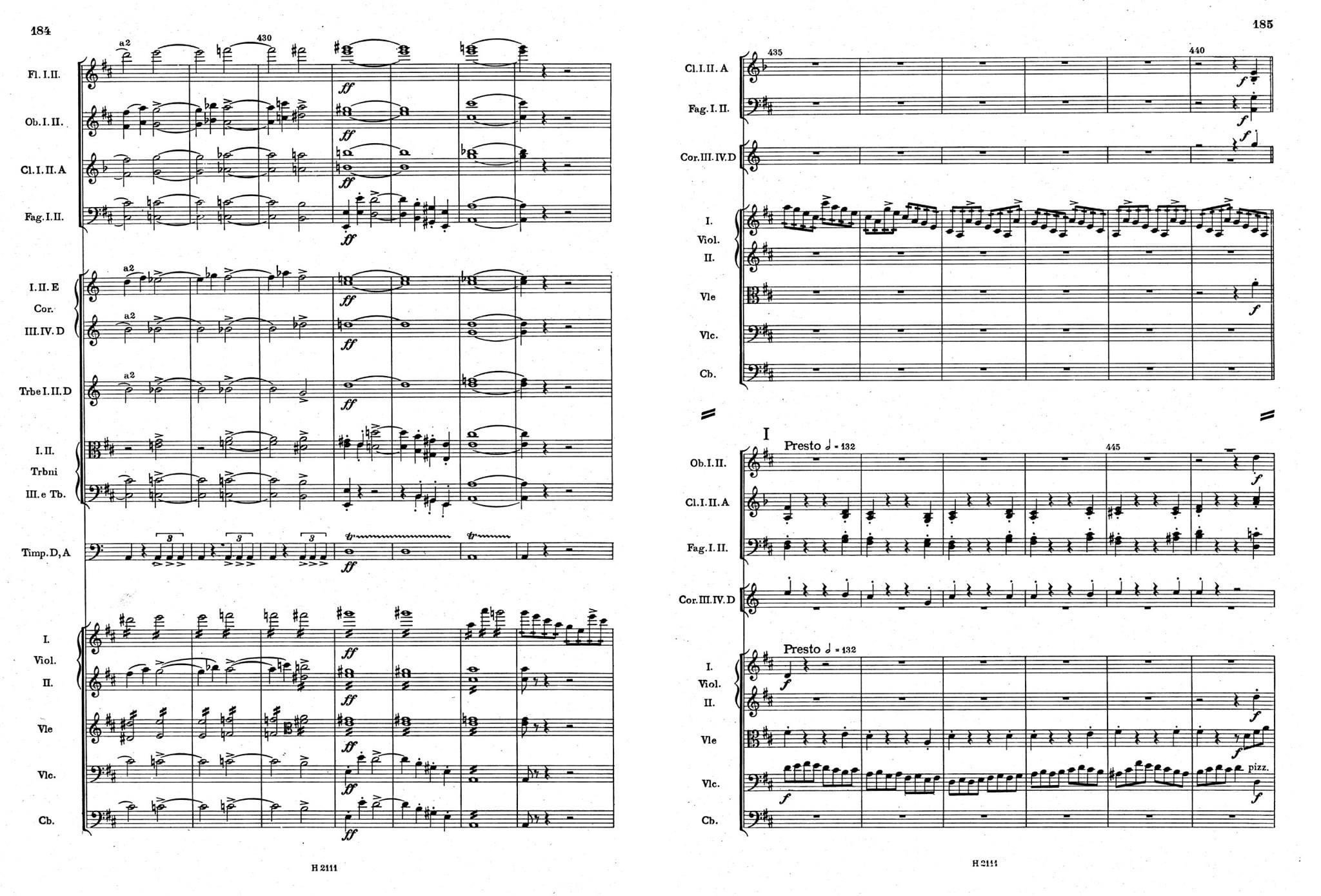

BARTÓK CONCERTO FOR ORCHESTRA, FINALE: TRIUMPH AND ELATION

Following a boisterous horn call, you are thrown head-first into a thrilling hora-like Romanian folk dance, leading to a riveting and expertly crafted succession of other Eastern European folk tunes. After 6 minutes of dazzling orchestral playing—just at the moment when you expect the final chords—you suddenly descend into the eerie world evoked in the earlier movements. After a few frightening moments in this disorienting world, a brilliant explosion blasts you home taking you from the depths of despair to the peak of elation. This final triumph over adversity brings closure to the entire work and leaves you exhilarated and empowered.

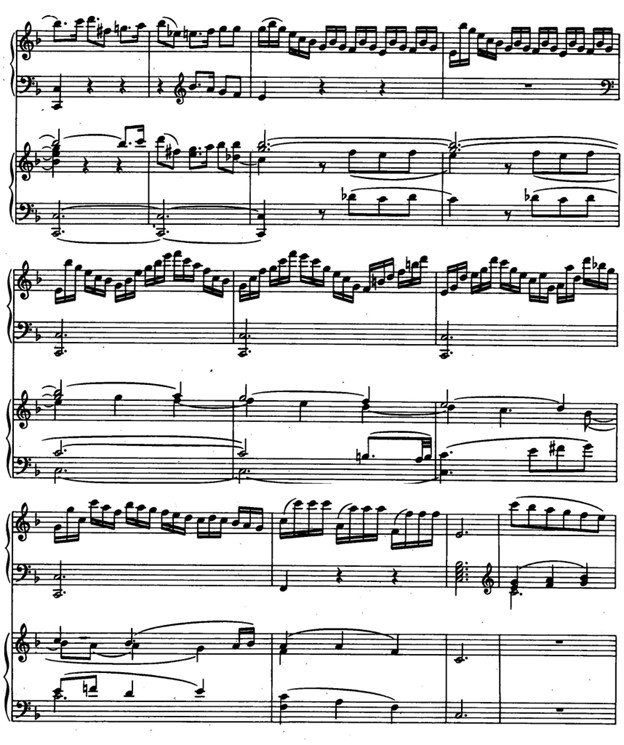

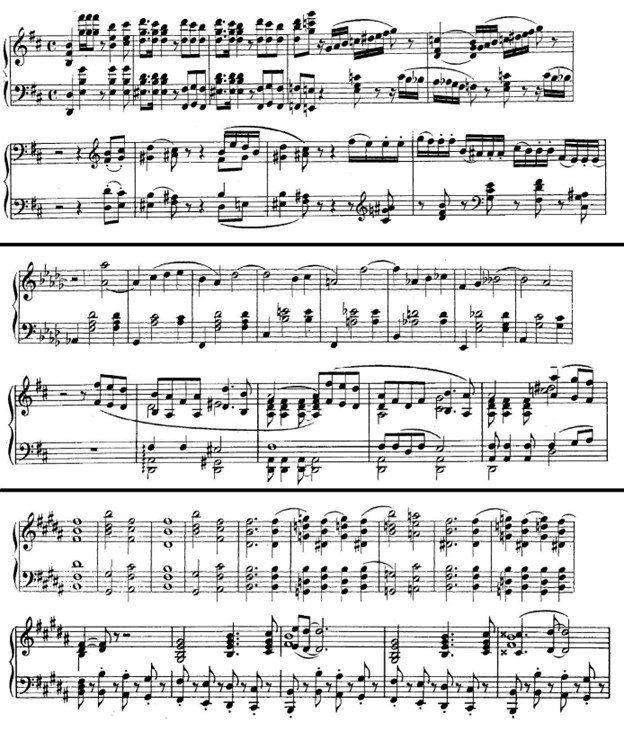

BACH VIOLIN CONCERTO NO. 1: EXHILARATION

You don't just listen to the music of J.S. Bach--you experience it. Not only does the music unfold elegantly from beginning to end right before your ears, but Bach elucidates this unfolding by binding brilliantly crafted contrapuntal elements within the melodic and harmonic framework of the work. As you traverse the cadences and climaxes, you feel Bach's counterpoint as an intense heartbeat guiding you through the twists and turns of the work, finally bringing you home. By baring its soul to listeners in this way, Bach's music brings a transparency and openness that is exhilarating.

This extreme openness in Bach demands a certain intimacy in performance. Reduced string sections, controlled vibrato, etc. are essential--not because of "authenticity" or HIP, but because the music, and the intimacy it demands, requires it.

It is also for this reason, that I prefer to "conduct" Bach from the harpsichord. For me, leading Bach from INSIDE the music as part of the basso continuo conveys the intimacy needed by the work, while contributing to the contrapuntal "heartbeat".

BEETHOVEN SYMPHONY NO. 5, 1ST MOVEMENT: A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH

From the very start you are hit with an explosive driving intensity held together with just enough control to keep the work from flying apart--a fragile balance that is relentlessly maintained throughout the movement. Creating this effect requires focus on such an extreme level, that the experience of the performer mirrors that of the listener—one of total commitment to a journey that is at once both frightening and exhilarating. To perform or listen to the work properly, you must feel as though it is a matter of life and death.

BEETHOVEN SYMPHONY NO. 9, 1ST MOVEMENT: SHATTERING BOUNDARIES:

That moment when silence becomes sound is elusive. Did we hear this sound start just now, or did we only just become aware of it? This anonymous sonority does not have the typical harmonic gravity towards another chord. It is the sound of eternity. But behind this sound is a gradual yet relentless growth in intensity that has even more direction than harmonic progression. This is pure, eternal energy, and as we progress measure-by-measure, we feel a sense of inevitability that something big is going to happen. When the first climax finally arrives, it shakes us to our core---it is the musical equivalent of a nuclear explosion. No amount of foreshadowing could have prepared us for this moment. Our expectations were set very high, and the work shattered them brilliantly.

Overall, Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is about exceeding expectation, breaking through boundaries, celebrating the limitless abilities of people and societies in achieving the unachievable. Beethoven took Schiller in “An die Freude” at its word, aspiring that the power of the individual can attain eternal brotherhood and transcend the limitations of our current world. Even for Beethoven, the composition of the Ninth Symphony itself, a combination of a Choral Setting of “An die Freude” with a full Symphony in D minor, represented his own aspirational goal—an accomplishment he dreamed about for many years and finally achieved.

Performers must strive to exceed listener expectation at every opportunity in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. In this opening moment, moving from the transition from silence to sound, through the unstoppable increase in intensity to the ultimate climax, must feel as though we have traversed from the depths of the ocean through the top of Mount Olympus in 26 seconds. If you haven't listened to this opening passage, do this now! It will take no more than a minute, but it will be an incredible experience!

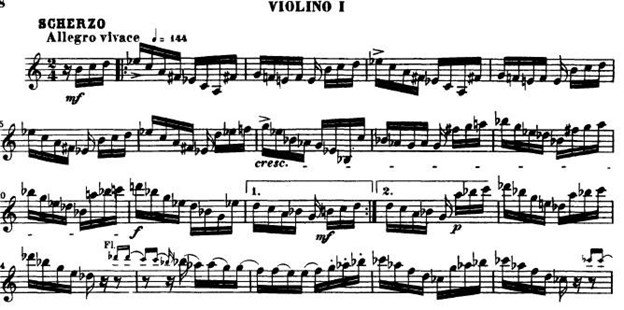

BEETHOVEN'S NINTH SYMPHONY, 3RD MOVEMENT: AN OASIS OF SUBLIME BEAUTY

Expressive appoggiaturas climb from ambiguity to a glorious tonal sunrise. This extraordinary unfolding introduces the Third Movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony—an oasis of sublime beauty sandwiched between the titanic expressions of fate and joy within the first, second and fourth movements. We are led from this introduction to a primary theme that is captivating in its lyricism and simplicity—whose elegantly spun long phrases are given an underlying vitality through a “heart-beat” pulse from the violas. This theme is embellished in a series of variations, but never loses the lyricism, vitality or underlying simplicity expressed the opening.

You may know this work from the Fourth Movement and its setting of Friedrich Schiller’s “Ode to Joy”, but take a moment now to listen to just the opening of the Third Movement. It only lasts a few seconds, and the worst thing that will happen to you is that you’ll be hooked and will be forced to spend about 15 minutes to listen to the whole thing. No downside, really…give it a try!

BEETHOVEN'S NINTH SYMPHONY, 4TH MOVEMENT: REACHING BEYOND THE STARS

The numerous settings of Friedrich von Schiller’s “An die Freude” to music in the late 18th Century did little to eschew its tagging as a drinking song. Even Schiller officially dismissed the work as “a bad poem” late is his life. It was Beethoven who altered the destiny of “An die Freude”—elevating the poem, and the music through which it is spoken in the Ninth Symphony, to an exalted status that continues to capture the hearts, minds and aspirations of people throughout the world.

The simplicity and elegance of the melody Beethoven chose to express the opening stanza of Schiller’s poem is infectious, having inspired adaptation into a widely popular church hymn “Joyful, Joyful” and its adoption as the Anthem of the European Union. As the listener progresses through the Symphony, Beethoven’s development and variations of this theme captivates and thrills us.

As exciting as these variations are, the defining moment of this movement is found elsewhere. Tucked inside a slower section just past the half way point in the fourth movement is a hymn-like passage with ascending chords through which we reach higher and higher, finally grasping as close to the heavens as mortals can possibly reach, while exclaiming the text “Beyond the stars He must dwell.” This is an extraordinary moment--both musically and spiritually. It is at this moment, where Beethoven reaches to the stars to touch G-d, where this Symphony reveals its soul. It is at this moment where we aspire to reach beyond our limits to achieve greatness. And it is at this moment where Beethoven frees “An die Freude” from its pedestrian past.

BIZET’S SYMPHONY IN C: A PRODIGY’S BRILLIANCE EXPRESSED THROUGH BREATHTAKING LYRICISM

Georges Bizet is best known as the composer of “Carmen”-- arguably the most popular opera performed today. But twenty years before the premiere of “Carmen”, Bizet composed his first and only symphony at the age of 17 while a student of Charles Gounod at the Paris Conservatory. The “Symphony in C” as it is known in the concert hall and in ballet houses thanks to George Balanchine, is an absolutely incredible work that not only weaves brilliance, beauty and passion through every note, but also demonstrates Bizet’s place as a prodigy of the highest order along with Mendelssohn and Mozart.

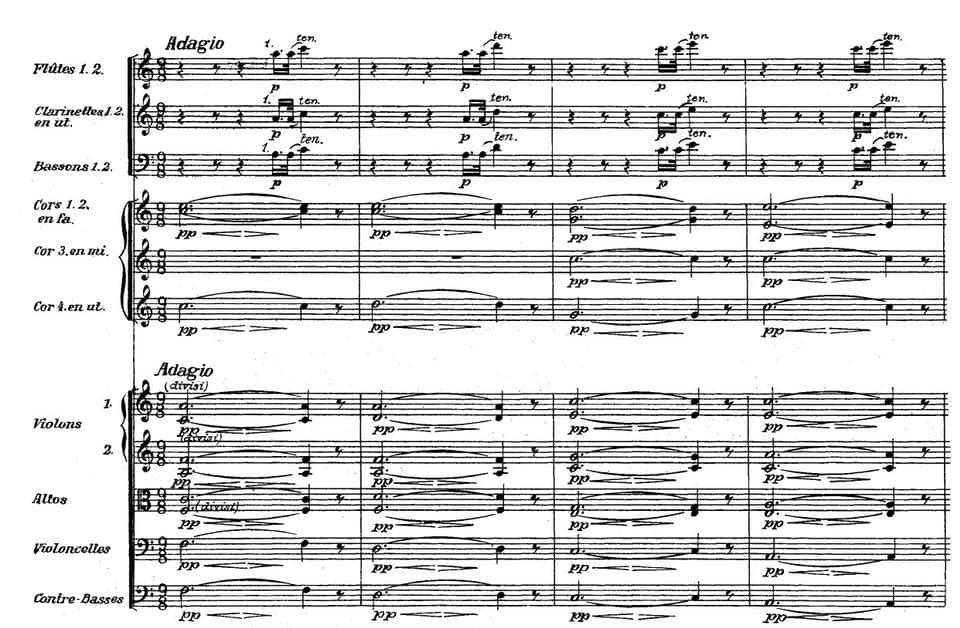

The entire work, from the first note of the energetic first movement through the last note of the blazingly brilliant finale, is hypnotically captivating. Of special note, however, is the second movement—Adagio—where Bizet creates a sound world encompassing a lyrical narrative that is simply breathtaking.

A mysterious exchange between winds and strings emerges, leading to the reveal of a lyrical theme played by a single Oboe over a bed of gentle pizzicatti in the strings. The Oboe line is so extended and sustained it is written for two players switching off to complete the entire phrase. The Violin sections take over, extending the lyricism and increasing the passion and intensity, drawing us through some of the most beautiful music ever written. I have to say this section never fails to send chills down by spine. A brilliantly conceived fugal section brings us back to a reprise of the opening Oboe solo, leading to an ending that evokes the opening. However, after having experienced the full narrative of this movement, this ending is no longer mysterious. Instead, it brings us closure.

The entire work is just over 30 minutes, and certainly worth listening to. But if you don’t have the time, at least listen to the 10 minute Second Movement. It will take your breath away.

STRANGERS IN A POLOVTSIAN PARADISE

Borodin begins his Polovtsian Dances with an introduction so lyrical and captivating, that Robert Wright and George Forrest couldn't help but steal it for their song “Strangers in Paradise” from the musical “Kismet”—making this melody one of the most recognized classical tunes of all time. This melody, played first by the oboe, then English Horn and finally the strings, is crafted to unfold so naturally that its beauty pulls you through the entire phrase from beginning to end. Popular? Sure--but also breathtaking. Give it a listen!

BRAHMS SYMPHONY NO. 2, 1ST MOVEMENT: SUBLIME BEGINNINGS

One of the most beautiful moments in music—a gesture from the lower strings introducing a sublime horn call—begins an alluring passage that unfolds with contributions from various sections of the orchestra. The eloquence of this opening—and of the entire symphony—is captivating. We are drawn in, deeper and deeper, step-by-step, into a sound world that takes our breath away.

BRAHMS SYMPHONY NO. 3: EXPERIENCING A SUBLIME WORLD

The musical narrative of this amazing work is nothing short of breathtaking. As we are led from beautiful moment to beautiful moment, we begin to wonder how the work can surpass itself as it continues to unfold---but it never fails to do so. And as the work progresses, and we are increasingly enchanted by its spell, we realize we are being drawn into a world conceived through a powerful underlying coherence.

The point at which this becomes clearest is as the end of the symphony. Just when you expect the work to begin its march towards an inevitably heroic ending, Brahms "switches the tracks" and brings the listener through a coda that dissipates the tension by unwinding. The work then begins to unravel, becoming more and more transparent, and just at the point of disappearing, the opening theme from the first movement is revealed as the symphony ends with soft ethereal chords in the winds and brass, escorted to closure by gentle timpani strokes. The effect is a sublime musical expression of eternity.

COPLAND APPALACHIAN SPRING: EXQUISITE EPILOGUE

The journey begins with three tones followed by rising chord rippling through the orchestra. The stark simplicity at the very start foreshadows a substantial narrative to come, from the innocence of day break through rustic dances, tragedy, intensity and a young couple’s wedding, leading to the beloved variations on a Shaker Melody called “Simple Gifts” that brings us triumphantly to the work’s climactic moment.

As popular and iconic as the “Simple Gifts” variations is—and for many “Appalachian Spring” IS “Simple Gifts”—the most extraordinary music of the work is yet to come. A heart-felt and introspective hymn emerges in the wake of this climax, escorting us through an epilogue that infuses a sense of empathy, note-by-note and phrase-by-phrase. The work begins to wind down, from a chorale to a solo voice, leading to a reprise of the rising chord rippling through the orchestra, this time more subtle. The work ends with three simple tones played by harp and bells before the orchestra fades into eternity.

This final 3 minute section, the denouement of the work, is expertly paced and crafted music that will never fail to send a chill down my spine, and often makes me a bit teary eyed....

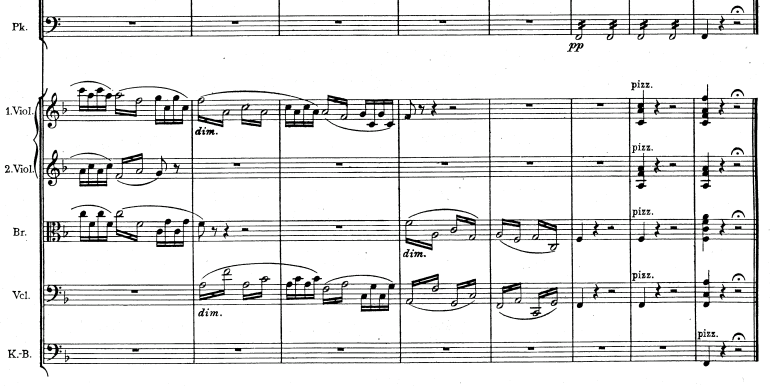

DVOŘÁK'S CELLO CONCERTO, 3RD MOVEMENT: THE POWER OF A SINGLE NOTE

Dvořák’s homesickness and unrequited love for his dying sister-in-law served as a powerful catalyst for the composition of perhaps his most personal orchestral work---his Cello Concerto. A profoundly personal statement of struggle and loss, the solo cello is often less an expression of virtuosity, than it is a narrator that escorts the listener through a spectacular journey imbued with sublime beauty and brilliance. While we experience many memorable moments along the way, the most powerful occurs towards the end of the work. After wistful phrases explore the depths of his pain and longing, Dvořák achieves transfiguration with an ethereal, hymn-like coda. But as the soloist and orchestra unwind towards the work's ending, the soloist plays a D-natural instead of the recurring D-sharps that preceded it. This single note, marked pianissimo, has the power of a bolt of lightning-- a shocking flashback to Dvořák’s painful struggles that drove him to leave New York City and return to Czechoslovakia. With one note, Dvořák reveals his soul. It is a profound moment that you must experience at least once! The Third Movement is only 13 minutes long, so give it a listen---but be sure to listen all the way through to catch this incredible moment.

DVOŘÁK SYMPHONIES 6 & 7: HIDDEN BRILLIANCE

Many believe that Dvořák’s symphonies fall into two categories---the great final two, and the remaining inferior seven. This view exists mainly due to our reliance on a skewed historical perspective—as we look back through history, it is difficult to see beyond Dvořák’s immense fame towards the end of his life, and the success of his 8th and 9th symphonies. His earlier works appear so small and distant in comparison, similar to viewing celestial objects light years away behind objects that are far closer. It doesn’t matter that the distant objects may burn hotter and are far larger than those closer to us--it is difficult for us to see this with the naked eye without examining them more closely. Our confirmation bias directs us to conclude that these objects, just as Dvořák’s first seven symphonies, are less significant, and in the case of Dvořák’s symphonies are of lower quality, because our surface view seems to support this conclusion.

Dvořák’s 6th and 7th Symphonies are mature and substantial works. Anyone who consumes them is instantly aware of their unique combination of brilliant episodes, riveting rhythmic tension and alluring lyricism. Most of all, the listener experiences countless breathtaking moments through a driving narrative that captivates from beginning to end---a combination I find to be irresistible and uniquely characteristic of Dvořák’s 6th and 7th symphonies.

The closing section of the final movement of the 6th symphony is a fantastic example of what makes these two symphonies so incredible, showing how Dvořák expertly crafts and paces his narratives for maximal engagement of his listeners. As the work unwinds towards its inevitable conclusion, the orchestra stops suddenly to reveal a brilliant display of fiendishly difficult arpeggios by the First Violin section. The listener is left both dazzled and perplexed, not knowing where the work will lead. Finally, we are brought to a blindingly fast perpetual motion, with each string section taking turns at playing virtuostic running lines. The energy and drive in this music is unceasing--moving through a brass fanfare that climbs higher and higher until we ultimately reach the work’s triumphant end. The elation experienced by both listeners and performers through these symphonic journeys is undeniable.

While his later symphonies inspire and delight us with beauty and innovation, it is his 6th and 7th symphonies that most clearly demonstrate Dvorak’s brilliance in crafting narratives with such power and direct impact on listeners. Give it a try!

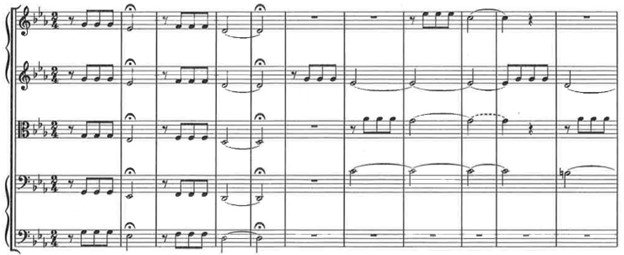

DVORAK SYMPHONY NO. 7: THE UNSUNG HERO:

Often standing in the shadow of Dvořák's extremely popular 8th and 9th Symphonies, is his 7th--a work so brilliant and captivating, that it grabs you from the first note and refuses to let go until the very last bar. Among the many incredible moments in this work is a passage in the second movement that is so breathtaking it never fails to bring chills, and maybe a tear or two. At just past the halfway point, a passionate, lyrical and chromatic passage in the strings gradually resolves into a reprise of the opening woodwind theme, this time written for the cello section. Everything about this passage---from its setting in the cellos to how the resolution of the chromaticism unfolds for the listener--is simply sublime. Go give it a listen---you will be hooked for life!

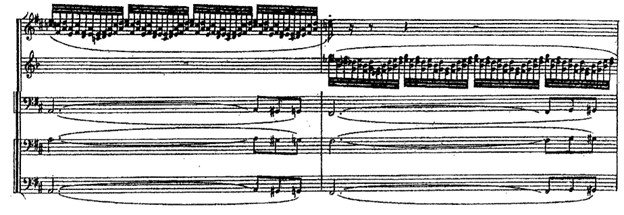

DVOŘÁK SYMPHONY NO. 7, 3RD MOVEMENT: DVOŘÁK'S CRAZY RHYTHM

The Scherzo of Dvorak’s 7th Symphony defies characterization in so many ways. It is certainly a dance, but is so much more. A unique rhythm starts quietly, yet firmly. As we proceed through each phrase, we become aware of the poetry and lyricism, but are also carried away by the driving, almost hypnotic pulse. The episodes bring us from the transparent and intricate to the blindingly brilliant and explosive in the blink of an eye, and just when the work is about to break apart, we land in a beautiful and lyrical trio section. In this alternate sound world, we hear echoes of the hypnotic pulse, but it is the quiet lyricism that carries us through, until we feel the intensity drive forward taking us back to a repeat of the opening section. After the triumphant conclusion, we feel as though we have been through a fantastic journey that couldn’t possibly be completed in a mere 8 minutes, but that is exactly what happened.

DVOŘÁK SYMPHONY NO. 8, 3RD MOVEMENT: DVORAK'S SONG WITHOUT WORDS

Dvořák’s Eighth Symphony suffers from the curse of familiarity and even then is seen as cowering in the shadow of the Ninth Symphony (“From the New World”). This is a shame, as it is in this symphony that Dvořák breaks his stylistic ties with Brahms, and develops his own voice through an innovative and absolutely beautiful work. It seems to be more of a fantasia than a symphony, with an excitement and poetry all its own.

Nestled within this work, where we would normally expect a brilliant scherzo (or in the case of Dvořák, a Slavonic Dance), we are treated to a hauntingly beautiful song without words infused with lyrical melodies across all sections of the orchestra. The trio is equally alluring—offering a ray of sunlight and warm optimism before gently returning to the song. Finally, Dvořák surprises us with a short scherzo-like Coda to close out the movement where we can just imagine him knowingly winking at us. This is truly a gem among Dvořák’s symphonic movements.

GERSHWIN CONCERTO IN F: CAPTURING YOUR HEART AND SOUL

In this wonderful Jazz/Classical "Fusion" concerto, the opening of the 2nd movement begins with an extended interlude of over 3 1/2 minutes featuring a solo trumpet accompanied by winds and lower strings. The poignant chromaticism of the accompaniment paired with the simple elegance of the solo line is an absolutely extraordinary combination of poetry and passion--pulling at your soul. For me, this is reminiscent of Scott Joplin's "Solace" -- which I adore for the same reasons. One has to wonder if Gershwin had "Solace" in his ears when he wrote this passage ("Solace" was written 16 years before the Concerto in F).

HAYDN SYMPHONY NO. 45 ("FAREWELL"): SWEET & SUBLIME GOODBYES

From the first note of the finale, you are shot out of a cannon with some of the most riveting orchestral music--an incredible mix of blinding energy and thrilling contrasts that take you from the depths of despair to an elation so intense your heart can't help but race. But just as you expect this work to end, something wonderful happens. Instead of the expected final chords, you are led to a slow minuet. The sublime music of this minuet is of such delight that you want it to go on forever--and for a time you feel a perfect combination of beauty and timelessness. But then you become aware that one by one, orchestra members stop playing. The music becomes softer and more personal, with the orchestra shrinking to a string quartet, then a trio and finally a duet of two violins--at which point the work ends.

The inevitable goodbye at the end of every work can be a bittersweet moment for the listener. We experience unimaginable beauty that is by definition accompanied by a desire for that experience to last forever, yet we know it will not. This work is extraordinary in how it shows so much compassion through the lengths it goes to prepare the listener for its ending. The moments of beauty and timelessness seem to say "enjoy this, for now" and the brilliant foreshadowing of the ending by dropping musicians one by one seems to say "its coming, and its OK" The result is a work that not only brings a sweet sense of closure, but also shows us how to savor each moment to its fullest.

It is only 7 minutes long and well worth the time. Go give it a listen for an unforgettable experience.

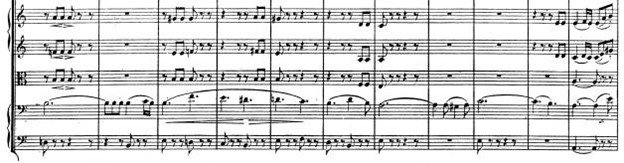

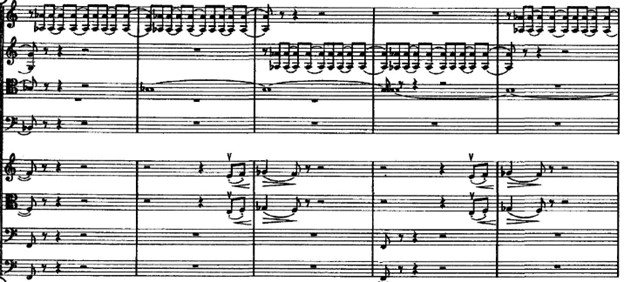

HAYDN SYMPHONY NO. 94, 2ND MOVEMENT: SUBLIME VARIATIONS

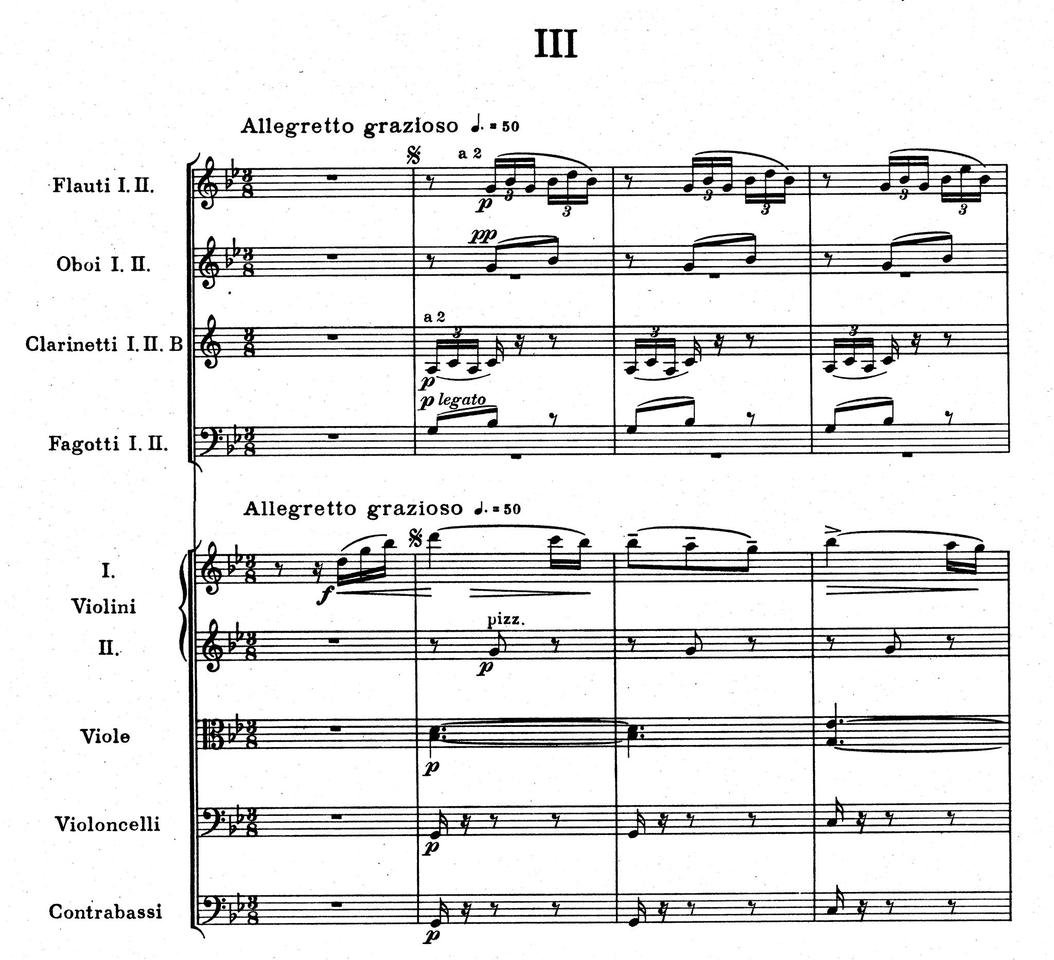

While no longer the surprise it once was, we still listen for that loud chord at the end of the first phrase with great anticipation. Yet the heart pounding adrenaline rush we experience is only the beginning. We are escorted through the remainder of this movement by a theme that on first glance seems so simple and ordinary, but for Haydn has limitless possibilities. Haydn's skillful rendering of these possibilities in a series of variations channels Bach here--on another level than the composers of his time.

As we progress, the variations unfold with more and more richness. Towards the end of the movement, we reach the variation depicted below, where the theme is paired with a brilliantly constructed counter melody in the flute and oboe. Here is where the most evolved setting of the theme is revealed--one that is both astonishingly beautiful and brilliantly conceived. It never fails to send chills down my spine.

While the opening of this movement is often played, you owe it to yourself to listen to this movement all the way through. You will not be disappointed.

HINDEMITH SYMPHONIC METAMORPHOSIS: BOISTEROUS, ROWDY AND INNOVATIVE TRANSFORMATION

Hindemith Symphonic Metamorphosis on Themes by Carl Maria von Weber is a wild romp through the mind of Hindemith that dazzles listeners with brilliant transformations of themes, settings and textures.

The whole work is enjoyable to perform and to listen to, but there is one moment in the second movement that never fails to blow me away. Just as it seems Hindemith has gone as far as he can go with his metamorphoses, he introduces a transformation of the theme in the trombones with a syncopated jazz feel that winds up being the subject of a fully developed "jazz fugue" featuring the entire brass section. Finally, the Timpani enters with the theme, which is somewhat extraordinary by itself, as timpani do not tend to play melodies---an amazing and unexpected moment!

TIME AND SPACE IN HOLST'S THE PLANETS

In 1949, the Austrian/American Mathematician Kurt Gödel used Albert Einstein’s equations from the General Theory of Relativity to prove the non-existence of time. In this proof, Gödel showed that within universes governed by the General Theory of Relativity, the past and the future could exist simultaneously. According to Gödel, “if time travel is possible, then time itself is impossible. A past that can be revisited has not really passed. Time is either necessary or nothing; if it disappears in one possible universe, it is undermined in every possible universe, including our own.”

Buried within the seven sound worlds that comprise The Planets—the angular driving energy of Mars, the gentle mysticism of Venus, the playful brilliance of Mercury, the gregarious optimism of Jupiter, the austere introspection of Saturn, the mischievous confidence of Uranus, and the boundlessness of Neptune—are references to both the past (Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, Dukas’ Sorcerer’s Apprentice) and the future (Copland’s Appalachian Spring, Bartok Concerto for Orchestra and John Williams’ Film Music for Star Wars and Harry Potter).

Attendees of the premiere of The Planets in 1918 experienced the past and the future simultaneously in the present, perhaps disproving the existence of time almost as effectively as the possibility of people completing a sufficiently long round trip in a rocket ship in Gödel’s universe traveling back to any point in their past.

As a result, Holst not only transports the listener to points beyond our familiar existence on Earth through distinctive use of color and masterful narratives, but also allows us to experience a few brief moments of eternalism where his masterful reinterpretation of the past, and his impact on the future of classical music intersect in a powerful musical temporal anomaly.

SCOTT JOPLIN'S ENTERTAINER: TEMPO, RHYTHM AND LYRICISM

Back in elementary school, we would compete to see who could play the Maple Leaf Rag at the fastest tempo without mistakes. When "The Sting" came out, our focus shifted to "The Entertainer". Ripping through the technical challenges of Joplin at breakneck speeds is exciting, and certainly develops eye-hand coordination as effectively as playing video games, but is devoid of any real music making. Anticipating the temptation to rip through his works, Joplin often used the tempo marking "Not Fast" to avoid this practice. Underneath all of Joplin's music is not only the trademark ragtime syncopated rhythmic tension, but also a sweet lyricism, both of which can only be realized effectively for the listener with slower tempi. When listeners hear Joplin performers savor every note, every rhythm and every phrase, the rhythmic sophistication and lyricism are brought together for a compelling and truly special musical experience.

SCOTT JOPLIN'S SOLACE: RAGTIME AS MEDITATION

This little gem--part slow ragtime march and part song without words--begins with simple chromatic lines spun with incredible skill that take you to a contemplative and wistful place. While poignant, and perhaps a bit lonely, it is also comforting--a meditation that brings closure to your inner most feelings. Just as the meditation ends, a gentle dance begins, offering a quiet expression of gratitude before the music stops, leaving you at peace. Namaste.

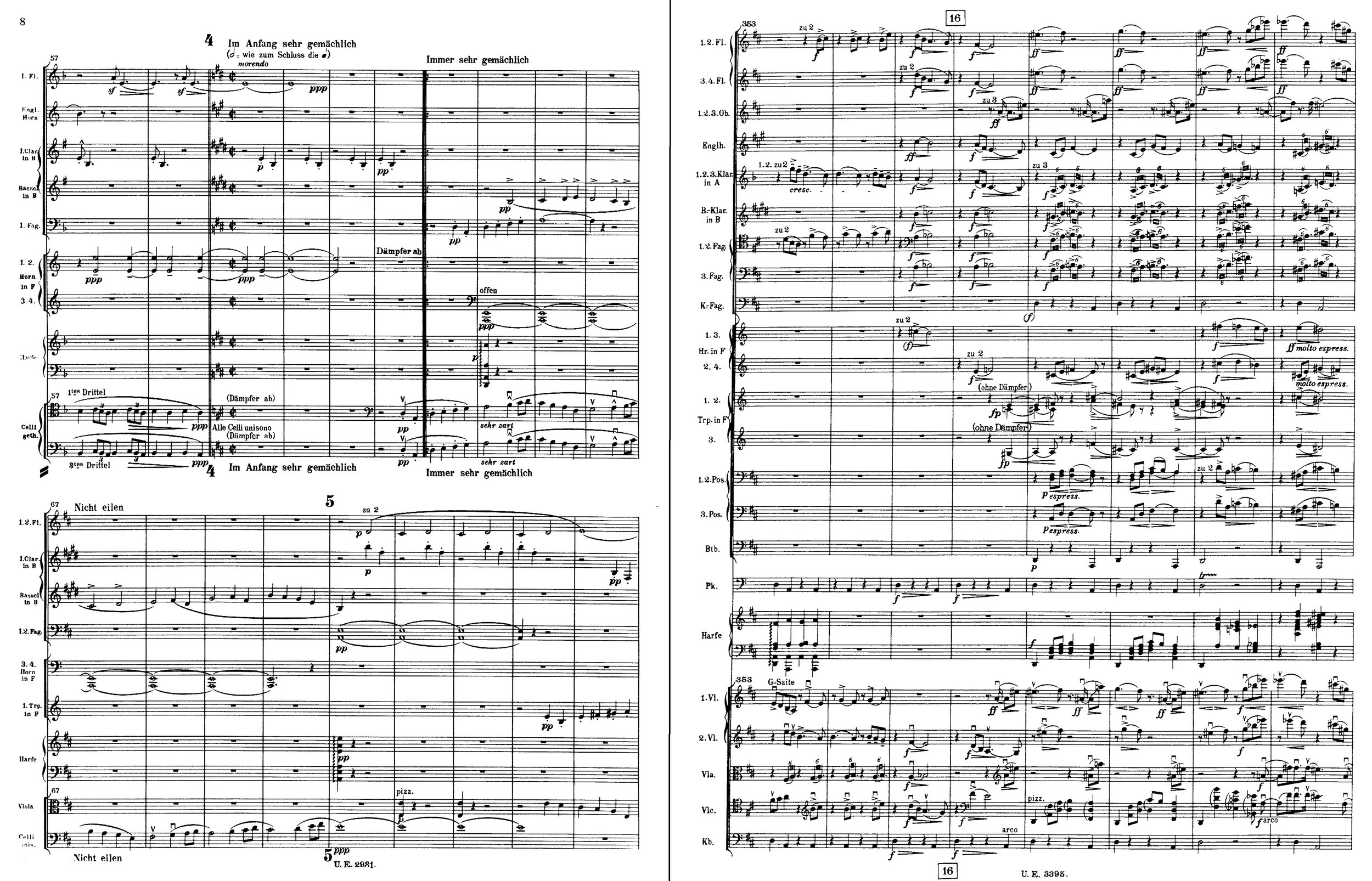

MAHLER’S JUNGIAN REVEAL: THE NINTH SYMPHONY’S “PAVANE”

It is telling to compare Mahler's First and Ninth Symphonies through the primary themes of their first movements. They are both “walking” themes, in the same key (D), that portray a young Mahler. Yet while the earlier version in the First has an innocent simplicity, the later version in the Ninth has more self-awareness and maturity. And in the Ninth, each time this theme returns, it brings more sophistication and complexity, leading to its breathtaking final statement at measure 353/#16. At this point the older, mature Mahler reveals the full picture of his younger self, with the Jungian Archetypes of his youth parading proudly to a version of the walking theme morphed into a “pavane,” with multiple layers laced through the full orchestra. What is extraordinary about this moment is how the difficult and awkward persona of his youth is portrayed with absolute clarity through an intense chromaticism that borders on the grotesque, yet that also feels at peace—as though Mahler has achieved a kind of acceptance of himself.

At 25 minutes, this first movement requires a bit of a commitment, but it is an experience to behold.

MENDELSSOHN SYMPHONY NO. 3, 1ST MOVEMENT: BREATHTAKING MOMENTS

An understated chorale walks us through a dark and mysterious place. We turn a corner, and are struck by a scene so stunningly beautiful that the shock of the moment sends goose bumps over our entire body. The feeling dissipates, and we continue walking, only to experience more and more striking visuals accompanied with progressively stronger reactions. Through this series of breathtaking moments during this 4 minute introduction, we are brought directly into a deeply moving and personal experience across sight and sound, yet conveyed only through the magic of music.

The whole work is absolutely incredible, but if you have limited time, just listen to the introduction. It is captivating and delightful!

MENDELSSOHN SYMPHONY NO. 3, 1ST MOVEMENT: SUBLIME TRANSFORMATIONS

There is no shortage of amazing moments in this deeply personal and mature work--yet one moment will literally send chills down your spine every time you listen to it. Two-thirds through this movement, as we move towards the recapitulation (where earlier material is repeated), the celli begin playing a lyrical line that grabs us with a seemingly impossible combination of simplicity and passion. As the celli continue playing after we reach the recapitulation, we are so mesmerized by their beauty that we do not hear a simple repeat of material. Instead, the haunting and seductive cello line transforms this passage into a delightful and stunning moment that we will always cherish as a listener. The first movement is only about 14 minutes long, and this moment occurs at around the 9 minute mark. Go give it a listen--you will not be disappointed and it is most certainly worth it!

MENDELSSOHN'S OVERTURE TO "A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM"—MAGIC AND MYSTICISM EXPRESSED THROUGH THE MUSIC OF A 17-YEAR OLD PRODIGY

A sound world is formed through a succession of mysterious woodwind chords. Then, in blink of an eye, this astounding work transports you through the twists and turns of a magical world infused with ethereal delights, introspective longing and joyous exuberance. Inside this work, you fully experience the 17 year old Felix Mendelssohn—both the brilliant composer who gracefully renders this multi-dimensional colorful musical realm with a mastery beyond his years and the teenager trying to making sense of his conflicting emotions and experiences.

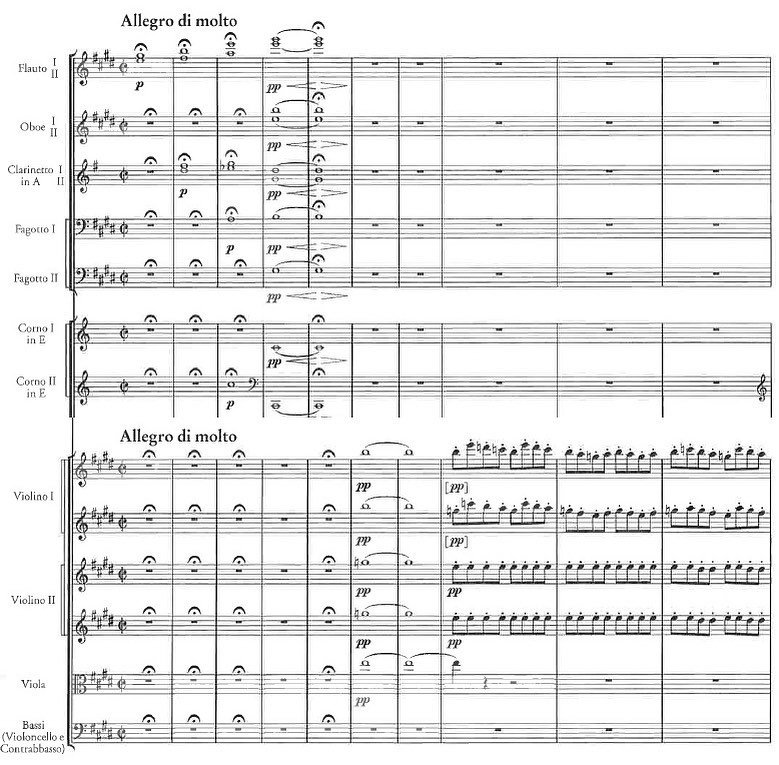

MOZART "JUPITER" SYMPHONY FINALE: EXTREME EXHILARATION

Some thoughts on Mozart Symphony No. 41 ("Jupiter") -- Each and every time I experience this symphony--as a conductor or as a listener--I am left with exhilaration that is so intense I feel like I am flying, Mozart brings energy, beauty and grace into perfect balance throughout the symphony, and dazzles us with a truly brilliant fugal coda that has become one of the best known passages in the symphonic literature. Mozart essentially fuses the formality of classical sonata form with unrelenting contrapuntal complexity--including demonstrations of contrapuntal techniques (stretto, inversion and retrograde), and finally bringing together five themes from this movement into a brilliantly executed double fugue.

Much of the praise of this work centers on its complexity---for example, Woody Allen is said to have exclaimed that this work proves the existence of God since only God could grasp its complexity.

But complexity alone cannot exhilarate. What dazzles us is how Mozart applies contrapuntal techniques and fugal writing in a surprising and unexpected way. At the point in the movement where the listener expects development to be slowed, Mozart does the opposite--incorporating a double fugue that accelerates the motivic development almost to the last bar. It is both a sophisticated and thrilling way to end not only this work, but also his entire symphonic output.

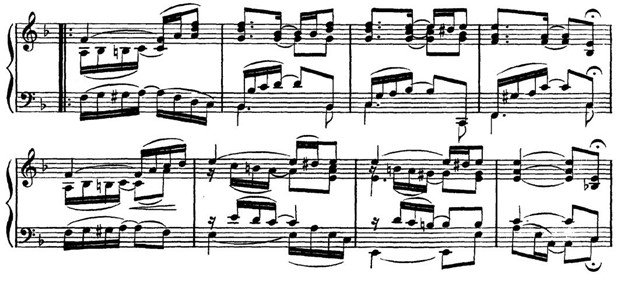

MOZART PIANO CONCERTO NO. 25, 2ND MOVEMENT: SUBLIME SIMPLICITY

Since an early age, Mozart wrote piano concerti to showcase his brilliance as a pianist. Initially formulaic and at least in several circumstances lacking in originality, the stream of piano concerti written towards the end of Mozart's life in 1785 and 1786—including nos. 20 through 25—blossomed in sophistication. While each of these concerti brought innovation and individuality offering much more than pianistic pyrotechnics, the 25th concerto stands out as the pinnacle of his achievements in this genre. In this most expansive of his piano concerti, Mozart draws you in from the first note to the last with an intoxicating mix of energy and lyricism, spoken with a voice that echoes the best of his symphonic and operatic writing.

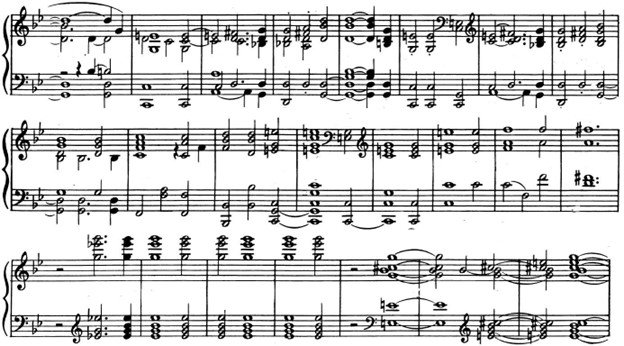

Inside this work, Mozart turns simple progressions into incredible moments, the most brilliant of which occurs halfway through the second movement in the excerpt shown. At this moment, the work is returning to the tonic key from the dominant. Mozart transforms this routine progression into an extraordinary journey for the listener—beautifully unfolding contrapuntally, drawing out the simplest of progressions into 10 sublime measures. While experiencing this passage, the listener is simultaneously aware of the inevitability of the goal of this passage, and grateful for every moment Mozart gives us to savor the beauty of the journey itself.

RAVEL DAPHNIS & CHLOE SUITE NO. 2: THE EXPERIENCE OF SUNRISE

We begin in darkness, but all is not silent. Despite the stillness of the early morning, our senses pick up the motion of dew drops, and we feel the continual, but subtle, activity of life and the world. The sky seems to brighten—a process that is not only ever so gradual, but also persistent. Birds start chirping after becoming aware of, or more accurately as part of, this stage in the process of the world. Finally, just above the horizon, the leading edge of light gives way to the emergence of the sun. We feel the importance of this moment as the sun’s warmth washes over us.

Only through music can we experience the full dimensionality of a sunrise--being shown with incredible clarity the changing effect and impact of its light through the passage of time from a first-person perspective. In the opening music to Daphnis and Chloé Suite #2, we not only see and feel the light, but also experience the impact of the light on the world.

RIMSKY KORSAKOV SCHEHERAZADE: TELLING A STORY THROUGH A SCALE

Storytellers transfix their audiences by illuminating powerful narratives from within the tales they tell. Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade portrays this ancient art musically with melodies that offer narratives worthy of the best storytellers. While there are many examples, the most compelling is the opening of the Third Movement—The Young Prince and The Young Princess. Just as a storyteller creates a transporting experience for their audience from a simple tale, this single gesture of 20 measures—from a pastoral beginning, through reflection, then passion and ultimately serenity—is woven from a simple descending 12 note scale. For me, this is not only an extraordinary musical representation of storytelling, it is also one of the most engaging moments in music.

SAINT SAËNS PIANO CONCERTO NO. 2: BEAUTY AND IMAGINATION

Instead of an orchestral introduction, this concerto opens with a solo cadenza that unfolds from a single note. As we are captivated by the soloist weaving lines of incredible beauty and imagination, we also realize it is not only this cadenza, but the essence of the entire work that is unfolding before our ears. Instead of reflecting on what we have heard as most cadenzas do, this opening cadenza drives and defines the work to come. It is an incredible and unforgettable moment that you must hear live!

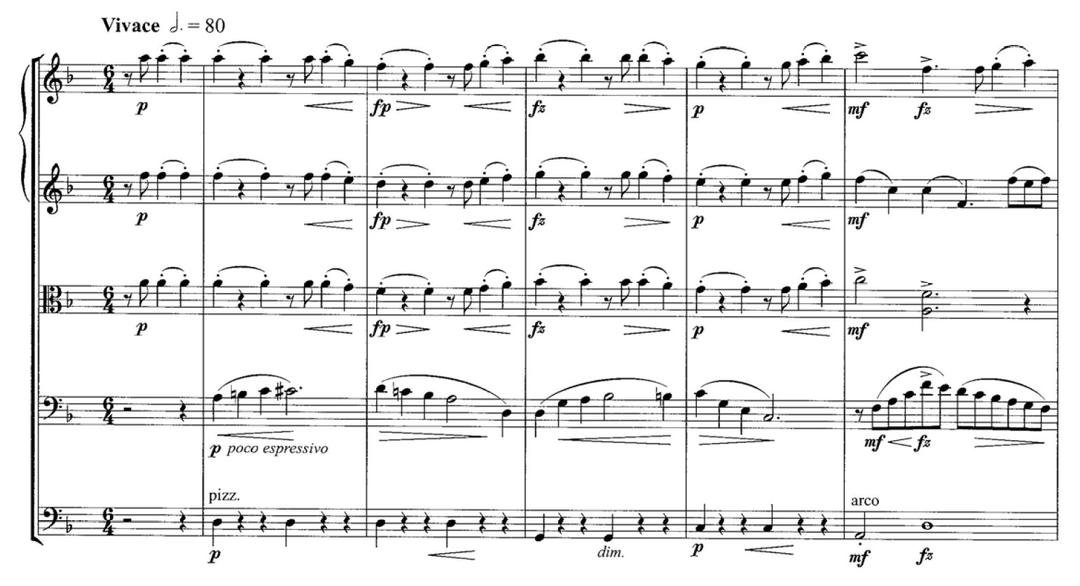

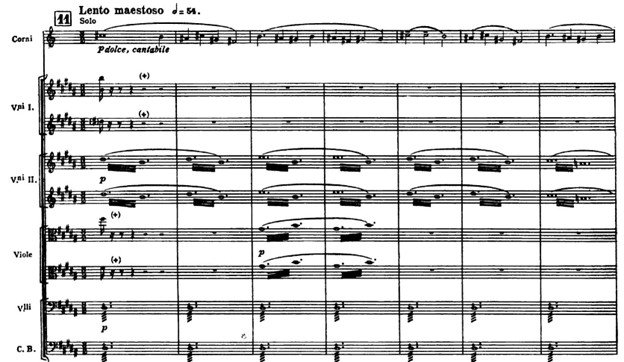

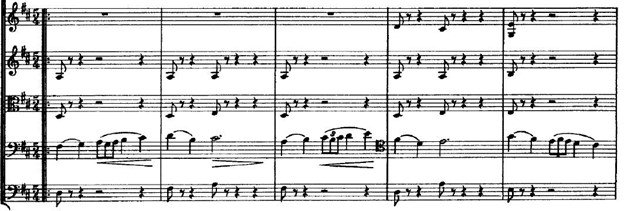

SCHUMANN SYMPHONY NO. 2: SCHERZO--THIS IS NO JOKE

The term Scherzo literally means "joke," but violinists never find this movement funny. These never-ending 16th note violin runs are fiendishly difficult and are found on most major orchestra's audition lists. Yet these passages woven throughout the movement represent more than technical pyrotechnics. They guide us through playful textures that are interlacedwith two beautiful trios---the first lighthearted and gentle, the second sublime and joyous--ultimately leading us to a coda. At this point the trumpets and timpani announce a suddenly faster tempo, introducing an even more spectacular perpetual motion from the violins. At this faster tempo, the violinists get the last word, driving us to a captivating, brilliant and thrilling conclusion (after which, if you listen very carefully, you will hear both violin sections exhale).

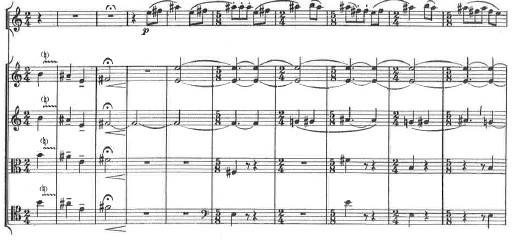

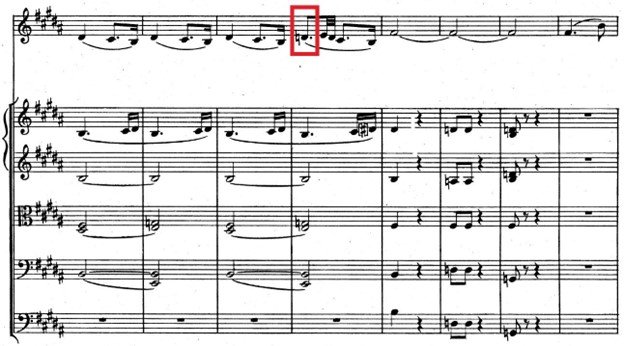

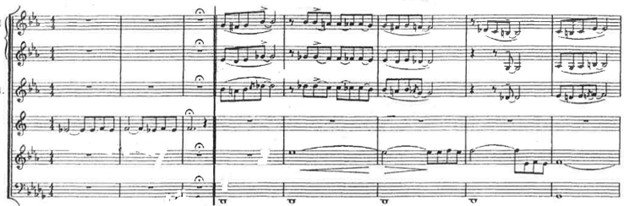

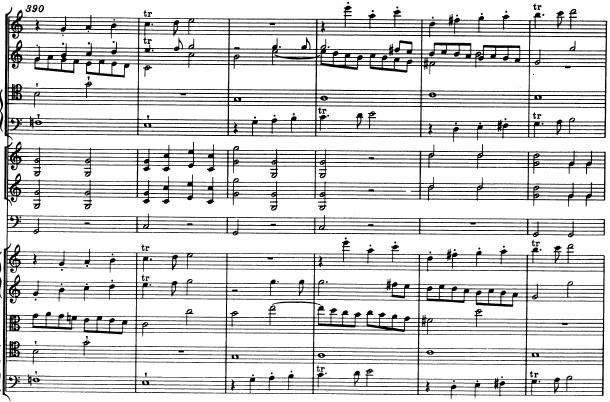

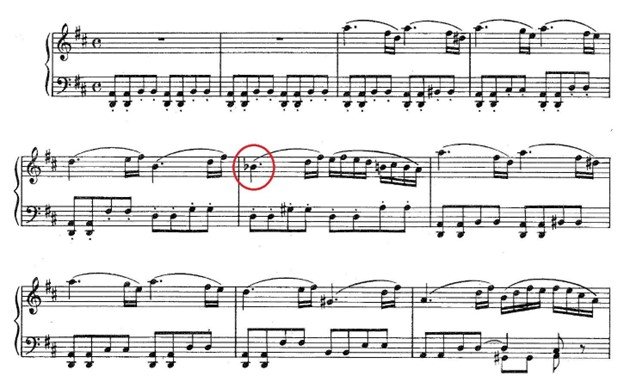

SCHUMANN SYMPHONY NO. 2, 3RD MOVEMENT: A SUBLIME MOMENT

There is so much to enjoy in this movement--from the molto espressivo violin theme taken from Bach's "The Musical Offering" that never stops pulling at your heart strings, to the poignant pulsating, heartbeat-like viola syncopations that sit beneath this theme, driving us to savor each moment. Great music never fails to surpass expectation moment-by-moment, and in this work, the third movement does not disappoint.

The most astounding moment in the entire symphony occurs in the third movement at measure 47 (the 5th measure in the photo I've posted). Approaching this moment, after moving through basic harmonies, the passage rests on a simple A-flat Major chord as time seems to stop. Then, out of this simple sound grows a sonority unlike any other--a sublime confluence of voice leading and harmonic necessity that takes your breath away. Schumann wanted this moment savored, as he added a "hairpin" under this chord--a crescendo followed by a diminuendo--to ensure that the sound is presented in all its glory to the listener.

A moment such as this should be experienced fully in real-time by the listener without regard to categorization or analysis. But if you were to "look under the hood" you would find that this chord is--note for note--an inversion of the famous "Tristan Chord." Or more accurately, Wagner's "Tristan Chord" is an inversion of Schumann's "Sublime Moment" chord, as Schumann's Symphony No. 2 predates Wagner's Tristan and Isolde by more than 10 years!

SIBELIUS SYMPHONY NO. 2: THE HEART AND SOUL FROM WITHIN

Sibelius draws us in with beautifully expansive music for strings that is entirely different than what we expect from the typical symphony-opening fanfares or lyrical songs. The gently pulsating richly scored ascending chords bring not only a sense of optimism but also motion—as though a warm breeze is gently and empathetically pushing us upward. As we experience this incredible music, we ponder whether we are hearing melody or accompaniment. These are just chords after all, but our experience with them has far more significance than a disembodied accompaniment. When the winds enter above this music with melodic material, we hear this more clearly as melody but are still not sure what to think of the opening material. Yet as we approach the end of this first movement--a brilliantly conceived journey that takes us on a vivid roller coaster of emotions lasting about 10 minutes—the music reveals what we suspected all along. The opening music for strings was the heart and soul of the entire movement and takes us to closure perfectly on the last note.

You never forget your first time listening to the opening of Sibelius Symphony No. 2

STRAVINSKY FIREBIRD SUITE (1919) FINALE: UNCEASING INTENSITY

After the listener is seduced by an alluring and passionate Berceuse, a disorienting mist of chromaticism leads us to a lyrical horn solo that marks the beginning of the work's Finale. Here we have one of the most exhilarating moments in music--the intensity builds constantly, note by note, phrase by phrase as the pacing speeds and our heart beats race. Just at the breaking point, the motion is stopped suddenly by an explosive string tremolo followed by a stately brass chorale that the leads us to the final chord. As this seemingly endless final chord grows with an almost unlimited intensity, we can't help but wish it would go on forever...

TCHAIKOVSKY SYMPHONY NO. 5, 2ND MOVEMENT: A JOURNEY FROM DARKNESS TO LIGHT

A succession of chords draws you down a dark path. The darkness heightens your senses, slowing down time, with each chord expressing its own world, its own eternity. The combination of darkness and beauty is tantalizing, leaving you strangely attracted to this place, but then, gradually, light emerges leading gently to one of the most beautiful and introspective melodies ever written.

The melody we finally reach, performed by the Principal Horn, is the best known feature of this symphony. But the approach to it is one of the most captivating moments in classical music. Take a listen--it only lasts about a minute....

THE ENIGMA OF TCHAIKOVSKY’S PATHÉTIQUE: FIRST MOVEMENT, REIMAGINING “ROMEO AND JULIET”

The creation of Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture was a protracted and difficult process for the young composer, mostly at the hands of his mentor Mily Balakirev. Their intense relationship began with Tchaikovsky destroying his score to his first tone poem “Fatum” after receiving scathing criticism from Balakirev, and continued when Balakirev suggested that Tchaikovsky write a work based on Shakespeare’s play Romeo and Juliet. Over time, Balakirev provided more hands on guidance, dictating the work’s overall structure, adherence to sonata form, relation of each section to the plot of Shakespere’s play and even which keys to use. What followed was a series of versions and revisions driven by detailed criticism transmitted by Balakirev to Tchaikovsky as he vicariously composed the work through Tchaikovsky’s hand. From start to finish, the composition of Romeo and Juliet spanned 11 years, from 1869 to 1880 across three versions, the third of which is frequently performed today.

The first movement of the Pathétique is clearly a reimagining of Romeo and Juliet. Both works are centered on the key of B minor with the Pathétique’s opening Allegro non troppo material mirroring Romeo and Juliet’s opening Allegro guisto in character and technique. Later, both works feature a theme whose exceptional passionate lyricism brings balance through its contrast with the urgent material that pervades this music. And both pieces end with an epilogue that puts the dramatic narrative in perspective. The relation between these two pieces is undeniable.

Yet there is an important difference. As exciting and brilliant Romeo and Juliet is, the work feels a bit contrived and uncomfortable in its skin—the result of Tchaikovsky’s 11 year struggle balancing his voice with Balakirev’s demands. And when considering Tchaikovsky’s later works, it seems as though the experience of writing Romeo and Juliet under Balakirev’s thumb caused Tchaikovsky to struggle more and more with balancing perceived external expectations for structure and form in his works, leaving an indelible mark on his output.

The first movement of the Pathétique is every bit as exciting as Romeo and Juliet, but feels more organic—as though it were driven by a single lightning bolt of inspiration. As it turns out, circumstances support this sense of the piece: Tchaikovsky wrote the first movement of the Pathétique in 5 days, from 2/4/1893 to 2/9/1893, in one continuous stream of consciousness across 19 pages in his sketchbook. And it shows---the first movement of the Pathétique is riveting from the first note to the last, without any sense of being contrived or scripted. Here, Tchaikovsky removed the shackles of external expectations and reimagined Romeo and Juliet as spoken through his pure artistic voice.

THE ENIGMA OF TCHAIKOVSKY’S PATHÉTIQUE: UNCOVERING THE HIDDEN PROGRAM

The search for the underlying meaning of works by composers of the past is difficult without the help of composers themselves. Notations in the score, correspondence or even second or third-hand reports of composer's statements can be invaluable. But what happens when a composer purposely hides the underlying meaning of a work?

In the case of Elgar’s “Enigma Variations”, Sir Edward Elgar proclaimed that the unifying force behind the entire work was an underlying theme that never appears in the work, which he refused to disclose to his dying day. The resulting mystery surrounding the work not only increased its popularity, but has driven an intense ongoing debate. In the case of Mozart’s “Requiem”, the circumstances around the commissioning of the work was kept secret as a requirement by the commissioner (Count Walsegg) who wanted to pass it off as his own. Mozart died after only barely getting started, requiring other composers to finish the work to complete the commission and allow his widow Constanze to be paid. After Mozart’s death, Constanze widened the deception, first by providing assurances that Mozart completed the Requiem himself to receive payment for the project, and then publicly promoting the notion that Mozart completed his Requiem in its entirety for himself on his deathbed after having been poisoned—a narrative that increased the popularity of the Requiem and allowed Constanze to claim ownership and secure income from publication and performance.

Mystery and intrigue sells, especially when the death of the composer is involved. It is also clear that when secrecy around the meaning of a work is permitted to linger, the void is filled by an imaginative public with, shall we say, alternative facts.

Tchaikovsky’s “Pathétique” Symphony brings a perfect storm of mystery and intrigue—combining aspects of both the “Enigma Variations” and “Requiem” deceptions. Similar to Elgar, Tchaikovsky publicly proclaimed an underlying program was embedded in the symphony, but refused to disclose it. And similar to Mozart, the proximity of Tchaikovsky’s death to the work’s completion—a death rumored to be a suicide—proved to be a catalyst for colorful theories by an adoring and imaginative public, including “Symphony as a Suicide Note” and “Symphony as a Lament of Forbidden Love.”

When experiencing the “Pathétique”, alongside the blinding extremes of energy, emotion and passion, the work feels stronger and more effective than his earlier works. Tchaikovsky’s other “mature” symphonies—the Fourth and the Fifth—while exciting, seem to struggle with balancing what Tchaikovsky wants to say with how he thinks he is expected to say it. The “Pathétique” makes direct references to these symphonies, but incorporates them through a more confident voice that is more at peace with Tchaikovsky’s vision.

A clue to the hidden program for the “Pathétique” can be found in the attached excerpt from the middle of the first movement. The horn section plays a rhythm reminiscent of Strauss Death and Transfiguration—a tone poem that depicts a dying man remembering his life, from his childhood through adulthood, and then, after dying, achieving heavenly transfiguration.

As the “Pathétique” progresses phrase-by-phrase through the first three movements, Tchaikovsky recalls his life through his music, reinterpreting his music without the boundaries he felt so strongly. We experience what Tchaikovsky would have written had he wrote what he wanted. When we reach the fourth movement, we meet Tchaikovsky in the present, at the end of his life. We feel the anguish and regret for not having said what he wanted to say, the elation he felt writing free of limits, and finally, the elation turning to acceptance and then to anguish with the realization he has run out of time to say more in this unrestricted voice. The fourth movement IS the symphony---where entire program is revealed, and Tchaikovsky’s true voice is heard

THE ENIGMA OF TCHAIKOVSKY’S PATHÉTIQUE: SECOND MOVEMENT, REIMAGINING THE WALTZ

Tchaikovsky may very well have been known as “The Waltz King” had Johann Strauss II not been given that title first. Tchaikovsky’s elegant and imaginative waltzes found within his ballets and operas are to this day some of his most popular and recognizable compositions—including the Waltz of the Flowers from the Nutcracker, Waltzes from Sleeping Beauty and Swan Lake, and his waltz from Eugene Onegin.

The second movement of the Pathétique symphony continues Tchaikovsky's recalling of his life through his compositions, this time with a focus on reinterpreting his waltz music without the limits of convention. Tchaikovsky did not label this movement a waltz, nor does the 5/4 meter used here typically evoke a dance. Yet from the first note to the last, Tchaikovsky’s innovation of expanding of each measure by two quarter notes brings a unique lightness and gracefulness to this movement that allows the theme to glide forward with an effortlessness that eludes most waltzes.

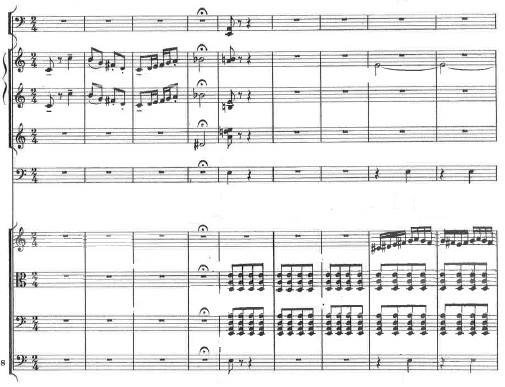

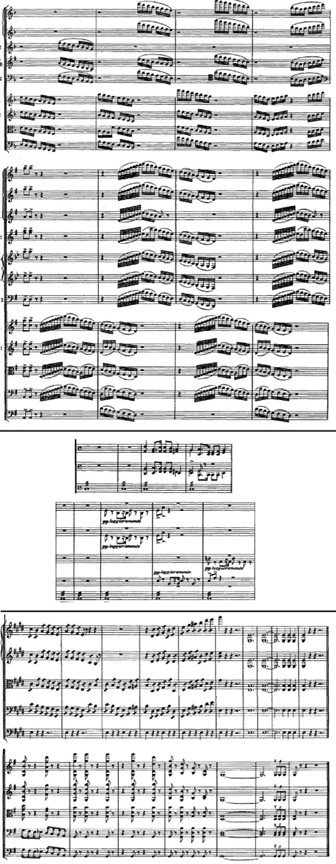

THE ENIGMA OF TCHAIKOVSKY’S PATHÉTIQUE: THIRD MOVEMENT, REIMAGINING THE SYMPHONIC FINALE

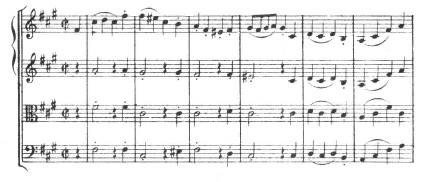

Tchaikovsky's next stop on his walk down memory lane that is his Pathétique symphony are his brilliant Symphonic Finales made famous through the final movements of his 4th and 5th symphonies.

Tchaikovsky's Symphonic Finales are certainly exciting, but tend to be long winded. The requisite combinations of contrasting material and formulaic development seems contrived, drawn out to conform to formal convention. The result is music that seems to be both self aggrandizing and uncomfortable in its own skin.

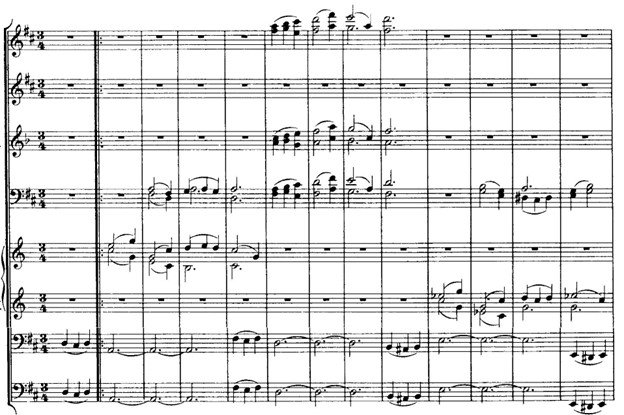

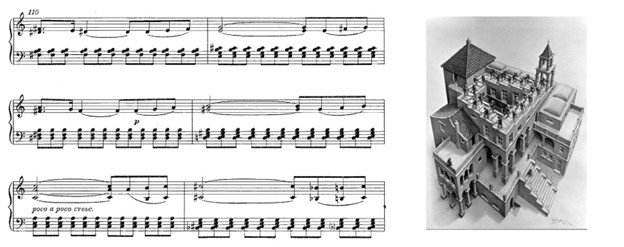

In the Third Movement of the Pathétique symphony, Tchaikovsky directly confronts the challenges in this music, dispensing with the formal constraints and taking the listener on a wild ride through an unrelenting stream of intensity at a level beyond what we have come to expect--even from Tchaikovsky. As we experience the thrill of this new take on the symphonic finale, throughout the movement Tchaikovsky reminds us that we are looking back on transformations of his earlier works by leaving us clues, some of which are shown in the image attached here.

However, the most startling change is that the work does not end with the final chords of this movement. Despite the exciting ending, we realize the work cannot end here, as we are inside a memory. We must still confront the present...

THE MAGIC OF THE NUTCRACKER: CELESTIAL SUGAR PLUMS

Perhaps the most well-known music from The Nutcracker is the Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy, capturing the listener’s imagination through exquisite use of the orchestra. As evocative as this music is, the story behind this music has a colorful drama all its own.

Choreographer Marius Petipa created the scenario for The Nutcracker that included this dance, leaving Tchaikovsky with the difficult challenge of portraying a dancing Sugar Plum Fairy musically. While traveling in Paris as he was mulling this over in 1891—just about a year before the Nutcracker’s premiere—Tchaikovsky encountered a small keyboard instrument called a Celesta, so named for the uncommonly magical “celestial sound” it creates. Tchaikovsky immediately knew the Celesta was the solution he was looking for, asking his publisher Jurgenson to acquire one for him in secret so it could be featured in the Nutcracker as an innovation, while not being pre-empted by Rimsky-Korsakov or Glazunov using the instrument first.

The ethereal and transparent sound world meticulously crafted by Tchaikovsky combining the high pitched ethereal Celesta, a lyrical bass clarinet and string pizzicati not only fits Petipa’s Nutcracker scenario brilliantly, but also established the music by which the Celesta has been known for over a century.

THE MAGIC OF THE NUTCRACKER: PART 1 -- ENCHANTING BEGINNINGS

Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Ballet is laced with magic and fantasy, from giant sized Christmas Trees, to nutcrackers coming to life and a land of the sweets ruled by a sugar plum fairy. For us, the real magic is created by the synthesis of dancers, the colorful costumes, the brilliant sets, the evocative choreography, and in no small measure, the brilliant score written by Tchaikovsky.

With the opening measures of Act 1, as Clara’s family prepares for a lavish Christmas Party, Tchaikovsky sets the mood with music that at once brings both a festive sparkle and a foreshadowing of the fantastic tale to come. The music begins with a simple melody that floats above a pulsating accompaniment, conveying a combination of joy and excitement. But towards the end of the first phrase, a tinge of chromaticism offers us a hint that all is not as it seems. This is only one example of how Tchaikovsky’s musical language expertly directs our perception of the drama unfolding around us. The entire ballet, not just the well-known suite, is an absolutely incredible multi-sensory adventure for audiences.

THE MAGIC OF THE NUTCRACKER: BEAUTY IN SIMPLICITY

The scale—a staple of musical study that resonates each day in practice rooms worldwide. But in Tchaikovsky’s hands in the Pas de Deux at the end of Act 2 of the Nutcracker, this most basic musical structure becomes poetry so exquisite that it leaves you with chills. Similar to a master painter turning a few primary colors into art, Tchaikovsky’s “artistic alchemy” expertly turns musical lead into musical gold.

THE MAGIC OF THE NUTCRACKER: MAGIC TREES AND FORESHADOWING ESCHER

A Christmas Tree grows from normal to gargantuan size, resulting in one of the most memorable moments of The Nutcracker. While set design plays a big part in the impact of this moment, it is Tchaikovsky’s score that enables the audience to visualize with absolute clarity the scope and scale of this magical transformation.

Depicting this moment requires conveying continual growth for an extended period of time, something that is difficult to portray in music due to the limitations of phrase lengths. But Tchaikovsky’s musical language knows no bounds, and succeeds brilliantly.

We begin by combining slowly rising legato lines in the upper voice with descending lines in the lower voice, a technique that allows the upper voice to sound as though it is climbing faster than it actually is. We then reach the climax of the first phrase with a cadence that feels as though we have arrived at a landing while climbing a flight of stairs—followed by the beginning of a new phrase that continues the climb. After three extended phrases and three full minutes of musical ascent, the music alone compels us to visualize the tree reaching its full size through an incredible and moving process.

In many ways, Tchaikovsky’s approach to convey the continual growth of the tree across multiple phrases foreshadows Max Escher’s Ascending and Descending, where the physical limits of height no longer limit continual ascent.

WAGNER'S PRELUDE TO TRISTAN AND ISOLDE: CAPTIVATING COUNTERPOINT

A wondering solo cello line leads us to a shocking sound. This is much more than a “chord”—it is a momentary confluence of voices whose powerful independence not only drives that shocking tension in that initial moment but is also manifested by their diverse trajectories. The sweep of this work resonates only when we fully harness the interdependence of these voices against each other—their lines, their pulse, their rhythms, both divergent and synchronous—in what is the most breathtaking and encompassing contrapuntal unfolding ever conceived.